Understanding Economic Cycles

Before we begin: We invite you to join our Free Telegram channel called 'Markets Daily,' where we provide daily market updates, macro insights, and investment opportunities. To subscribe, please click the link below:

1. Introduction: The Dynamics of the Economy

The global economy is not a static entity but is subject to constant movement, manifesting in recurring patterns. These wave-like fluctuations in overall economic activity are known as economic or business cycles. Understanding them is fundamental for all stakeholders – from businesses to policymakers and investors – to make proactive and informed strategic decisions.

The business cycle describes the regular sequence of high and low phases within the economic circuit. It represents the continuous upswing and downswing of economic activity. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) experiences phases of growth and decline over time, which defines this cycle.

A deep understanding of the economic cycle enables companies to act proactively rather than reactively, make better business decisions, and thus contribute to long-term profitability and stability. Economists, entrepreneurs, and investors use economic indicators to assess the state of the economy, better understand stock market developments, and make the right investment decisions. Governments, financial institutions, and investors act differently throughout business cycles, highlighting the need for an adapted strategy.

The inherent cyclicality of the economy, although varying in duration and intensity, implies a fundamental predictability. By recognizing these patterns, economic actors can shift from reactive crisis management to proactive strategic planning. This allows for mitigating risks and optimally utilizing opportunities in the various phases of the cycle. The ability to act foresightedly is crucial for long-term success in a dynamic market environment.

2. The Four Phases of the Business Cycle in Detail

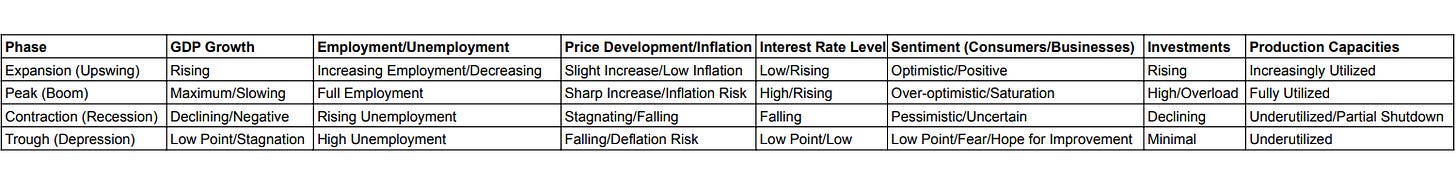

A typical business cycle is traditionally divided into four main phases: Expansion, Peak, Contraction, and Trough. Each of these phases is characterized by specific features and dynamics that affect the entire economy.

2.1. Expansion (Upswing)

Expansion marks the beginning of a steady positive development of the economy. In this phase, the economy begins to flourish, characterized by increasing economic growth. The demand for goods rises , leading to growing production capacities. This, in turn, leads to a positive development in employment: unemployment is stable or even decreases.

With rising employment, people have more money, which boosts consumption. Companies seek investments , and prices only increase slightly. Interest rates are low but show an upward trend. The economic sentiment is positive and optimistic , and stock market prices are also on an upward trend.

2.2. Peak (Boom)

In the peak phase, the economy reaches its highest point. Production capacities are fully utilized , and there is nearly full employment. High corporate profits lead to rising wages and a stable employment rate.

Prices and interest rates continue to rise. In this phase, there is a risk of the economy overheating, which can lead to high inflation rates and speculative bubbles. This often leads to over-optimistic expectations and misinvestments.

2.3. Contraction (Recession)

A recession describes the contractive economic phase in which a decline in economic activity is recorded. Usually, a recession is defined as a period when the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) shrinks for two consecutive quarters compared to the previous quarters.

In this phase, the boom weakens, and forecasts for the economic situation become pessimistic. Demand declines , inventories fill up , and production is scaled back. Unemployment rises , and short-time work is introduced. Investments decline. Prices, wages, and interest rates stagnate or fall. Stock market prices fall.

2.4. Trough (Depression)

The depression is the low point into which an economy falls due to a downturn. Overall economic activity declines over a long period. Demand for goods and services is very low.

Unemployment is high. Prices and wages are low, and deflationary tendencies emerge. Investments are minimal. Fear-driven saving sets in. Low interest rates make money cheaper and normalize the relationship between supply and demand. This leads to a "market clean-up," where companies with non-functioning business models exit.

Economic cycles are not solely the result of objective economic factors but are significantly influenced by collective psychological dynamics – such as consumer and business confidence. These sentiments can act as self-fulfilling prophecies, amplifying upswings and deepening downturns. Over-optimistic expectations can lead to misinvestments, while widespread pessimism can exacerbate a recession. Managing expectations thus becomes a critical element of both economic policy and corporate strategy.

The trough phase, as challenging as it may be, functions as a crucial "cleansing mechanism" of the market. The correction of overvaluations, reduction of costs, and exit of inefficient companies create a healthier foundation. This allows for a normalization of the supply and demand relationship and prepares the ground for the next recovery phase, underscoring the inherent resilience of market economies. This process, though painful, is essential for the long-term adaptability and vitality of an economy.

Overview of Business Cycle Phase Characteristics

3. Types and Duration of Economic Cycles

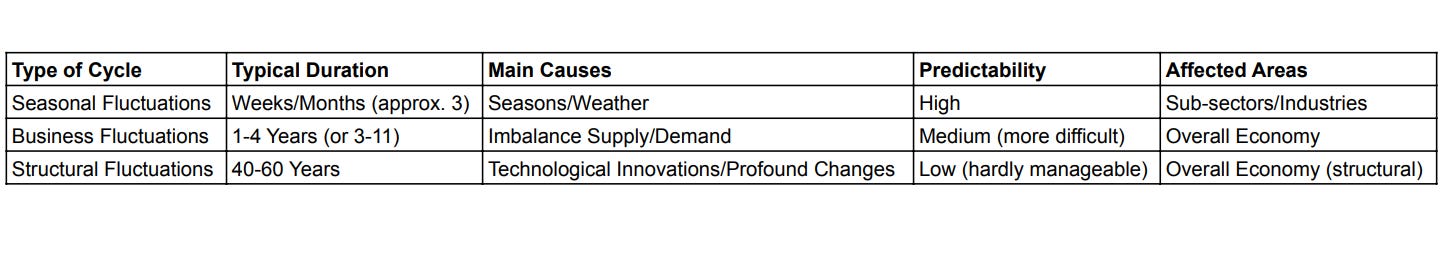

Economic cycles are not monolithic; they vary in duration and causes. Economics typically distinguishes three main types of fluctuations, which have different implications for planning and management.

3.1. Seasonal Fluctuations

Seasonal fluctuations are the shortest cycles, often lasting only a few weeks or months, typically about three months. Their causes primarily lie in the seasons and weather conditions. They mostly manifest as upswings or downturns in specific sectors of the economy. Examples include the highs and lows of the construction industry in summer and winter or the Christmas season for retail. The advantage of seasonal fluctuations lies in their relatively high predictability, which allows individual industries to prepare well.

3.2. Business Fluctuations (Medium-Term)

Business fluctuations are medium-term in nature and typically last between one to four years , but can also range from 3-5 years , 6-10 years , or 7-11 years. They are mainly caused by an imbalance between aggregate demand and aggregate supply, with time lags in adjustment having a significant impact.

Within this category, specific cycles are distinguished: The Kitchin cycle, with an empirically proven length of 3 to 4 years, is used to assess business production and sales planning as well as inventory management. The Juglar cycle, lasting between 6 and 10 years, describes investment phases. Unlike seasonal fluctuations, business fluctuations are more difficult to predict.

3.3. Structural Fluctuations

Structural fluctuations are long-term in nature, extending over periods of about 50 to 60 years. They are triggered by profound changes and innovations in key technologies. A basic innovation must be accepted and used by the broad masses to bring about sustainable expansion.

Historical examples of such cycles include the invention of the steam engine, the dominance of railways and steamships, the development of electrical engineering and heavy machinery, and the era of affordable energy and cars. Current experts assume that digitalization and innovative green technologies could trigger the next of these positive waves, which is referred to as the "Green Kondratiev" phenomenon. These fluctuations have major impacts on the labor market and the production potential of an economy. Policy can hardly intervene in a shaping manner here, as these are fundamental, long-term transformations.

Beyond short- and medium-term fluctuations, structural cycles, especially the Kondratiev waves, are proof that technological innovations are the fundamental, long-term drivers of economic transformation. These "basic innovations" not only improve existing processes but create entirely new industries and paradigms that fundamentally reshape the economic landscape over decades. This underscores the crucial role of research and development and innovation-promoting policies for sustainable prosperity.

Classification of Economic Cycles by Duration

4. Drivers and Early Warning Systems of the Economy

The economy is influenced by a variety of interdependent factors. To anticipate and understand its development, so-called economic indicators are essential. They serve as early warning systems and provide information about the current and future economic situation.

4.1. Fundamental Influencing Factors

Private household consumption represents a central driver of demand and thus production. In parallel, corporate investments, the development of national and international companies, including interest rates and wages, as well as imports and exports, significantly influence the economy. It should be noted that investments are among the most volatile components of Gross Domestic Product.

Government spending, economic policy, and tax burdens have a direct impact on aggregate demand and the economy. Future expectations and consumer confidence are also crucial, as the sentiment and expectations of actors (businesses and consumers) can initiate turning points in the economy.

Long-term structural fluctuations are triggered by technological innovations that increase production potential and create new industries. Finally, global events and political developments such as financial crises, geopolitical tensions, pandemics, or election results can significantly influence local and global cycles and act as external shocks.

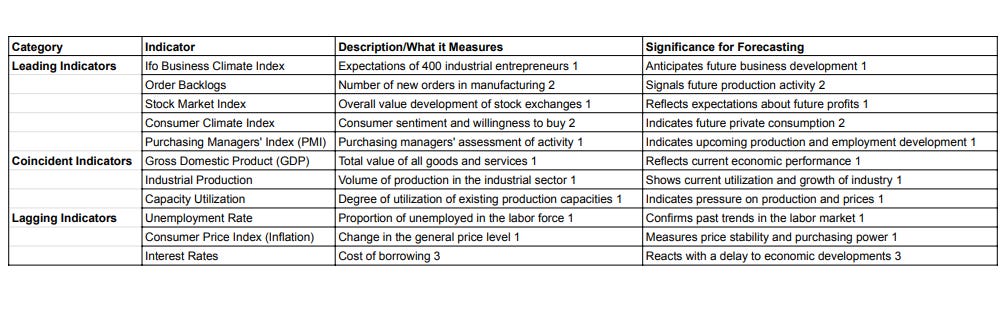

4.2. Role of Economic Indicators

Economic indicators are key figures used to capture an entire economy and provide information about its development. They help predict possible changes. These key figures can be divided into three categories:

Leading Indicators: These indicators show future developments and precede the economic trend. Examples include order backlogs in manufacturing, stock indices, the consumer climate index or consumer confidence, the ifo Business Climate Index, and the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI).

Coincident Indicators: These indicators provide information about current overall economic developments and change in sync with GDP development. These include consumption figures , capacity utilization , total industrial production , and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) itself.

Lagging Indicators: These indicators lag the economic trend and confirm the corresponding economic situation with a time delay. Typical lagging indicators include the unemployment rate, interest rates, and the Consumer Price Index / inflation rate.

Effective economic forecasting and strategic decision-making require a nuanced understanding of both "hard" economic data (e.g., GDP, industrial production) and "soft" sentiment indicators (e.g., business climate, consumer confidence). Leading indicators, often sentiment-driven, anticipate future trends, while coincident and lagging indicators confirm current and past conditions. The market's reaction to deviations from expectations underscores the need to interpret these different data points in conjunction to obtain a comprehensive and timely economic perspective.

Economic cycles are not exclusively organic phenomena but are significantly shaped by political decisions and geopolitical events. Government spending, tax policy, and central bank actions can accelerate or slow down economic phases. Furthermore, unforeseen political shifts or global conflicts can act as significant external shocks that abruptly change the course of a cycle. This illustrates the dynamic and often unpredictable interaction between economics and politics.

Key Economic Indicators and Their Classification

5. Policy Responses and Management of Economic Cycles

Governments and central banks employ a range of instruments to manage the effects of economic cycles and promote overall economic stability. These measures, known as monetary and fiscal policy, play a crucial role in dampening fluctuations.

5.1. Role of Monetary Policy (Central Banks)

Central banks primarily pursue the goal of price level stability with their monetary policy, preventing both excessive inflation and deflation. Furthermore, they support objectives such as economic growth, stable exchange rates, and the functioning of financial markets.

Interest Rate Adjustments: A key instrument is the adjustment of key interest rates. By lowering interest rates, growth can be stimulated during economic downturns, as loans become cheaper, thereby encouraging investment and consumption. Conversely, raising interest rates during expansions can help prevent inflation and an overheating economy by dampening credit demand.

Quantitative Easing (QE): When traditional interest rate cuts reach their limits (e.g., near the zero lower bound), central banks resort to quantitative easing. This involves them buying large quantities of government bonds or other securities from financial institutions. The aim is to increase liquidity in the banking system and keep long-term interest rates low to stimulate lending, investment, and consumption. This can also lead to rising prices in financial markets. However, QE also carries risks, such as asset overvaluation (bubble formation) and the risk of a subsequent crash. Moreover, banks may hold back excess reserves, which can limit the program's effectiveness.

5.2. Role of Fiscal Policy (Governments)

Fiscal policy is an economic policy instrument of the state that, by influencing taxes and government spending, attempts to balance economic fluctuations and achieve stable economic growth, high employment, and low inflation.

Instruments (Counter-cyclical Fiscal Policy): The state usually acts counter-cyclically, meaning measures are used against the current economic trend.

Expansionary Measures (in Recession): To stimulate the economy during downturns or depressions, the state increases its spending (e.g., through public contracts, expansion of social benefits, promotion of employment programs, infrastructure investments) and lowers taxes (e.g., income or consumption taxes). This is intended to stimulate aggregate demand.

Restrictive Measures (in Boom): In phases of high economic activity, fiscal policy is used restrictively to slow down the economy and prevent overheating. This is done by reducing government spending (e.g., cutting subsidies, reducing social programs) and/or increasing taxes and levies. The goal is to build financial reserves for future recessions.

Stimulus Packages: Specific stimulus packages, such as "green stimulus packages," attempt to combine short-term stabilization with long-term sustainability goals.

Challenges: The design of fiscal policy is complex. Measures take time to take effect (time lags), which makes choosing the right timing difficult. In addition, many government funds are tied up long-term, which limits rapid responsiveness. Social acceptance, especially for tax increases, can also hinder implementation.

The effectiveness and timing of political measures are crucial. Time lags in implementation and effect can mean that measures only take effect when the economic situation has already changed, potentially exacerbating rather than smoothing fluctuations. This underscores the complexity of economic policy, which often represents a balancing act between necessary interventions and potential undesirable side effects.

Monetary and fiscal policies are closely linked and overlap in their areas of influence. For overall economic stability and the utilization of growth opportunities, coordinated and sustainable implementation of both policy areas is required. A lack of fiscal policy sustainability can overstretch monetary policy, while uncoordinated action can create conflicts of objectives. Effective economic analysis must therefore consider the dynamic and often unpredictable interaction between economic variables and political and geopolitical decisions.

6. Impact of Economic Cycles on Sectors and Investment Strategies

Economic cycles affect different sectors of an economy differently and require adapted investment strategies.

6.1. Sectoral Impacts

Technology: The technology sector is particularly susceptible to cyclical fluctuations. The late 1990s and early 2000s, for example, experienced a technology boom followed by a subsequent collapse of the dot-com bubble. Technological advancements, such as the internet and digital technologies, transform sectors and create new opportunities, but also challenges throughout the cycle. In expansion phases, cyclical industries like electronics and automotive benefit.

Manufacturing Industry: The economic strength of an economy is measured by its production capacities, whose utilization directly indicates the economic situation. In an upswing, production, demand for goods, and employment rise. In a downturn, however, production and orders decline, inventories fill up, and unemployment rises.

Service Sector: The service sector, particularly areas like hospitality and entertainment, is sensitive to changes in consumer spending patterns. The share of equipment investments in the service sector has increased significantly in recent decades and contributes significantly to fluctuations in the growth rate.

Financial Sector: The stock market often acts as a leading indicator for the business cycle, as investors incorporate their expectations about future economic developments into their buying and selling decisions. Bull and bear markets influence investor confidence and thus spending. Financial crises, such as that of 2008, can be triggered by problems in the financial system and lead to severe recessions.

The differing reactions of sectors to economic phases are evident. While cyclical sectors like technology and manufacturing flourish in expansion phases, defensive sectors such as pharmaceuticals or utilities prove more resilient in downturns. This highlights the need for strategic sectoral allocation and broad portfolio diversification to minimize risks and capitalize on opportunities in all phases of the cycle.

6.2. Investment Strategies in the Phases

Different phases of the economic cycle require adapted investment strategies. Broad diversification across various asset classes is fundamental to spreading risks.

Equities:

Expansion: In the expansion phase, sentiment is optimistic, and wages and consumption rise. This is a good time to invest in stocks and funds of cyclical industries such as electronics, automotive, and technology, as they benefit from the general market euphoria.

Boom: In the boom phase, the market approaches saturation, and many stocks may be overvalued. Caution is advised here; investments in "hyped" stocks carry the risk of losses, as the dot-com bubble showed. A conservative investment strategy with broadly diversified ETFs and government bonds is more advisable.

Downturn/Recession: During a downturn, stocks and funds of counter-cyclical companies (e.g., pharmaceutical companies, energy providers, food companies) are worthwhile, as they are considered independent of the economic cycle. Value stocks, which are often undervalued in recessions, can be attractive in this phase and benefit from a later recovery. For long-term investors, downturn phases historically offer good opportunities to acquire high-quality stocks at reduced prices.

Late Cycle: In the late phase of the business cycle, quality stocks historically achieve the best risk-adjusted returns, while value and small-cap stocks tend to lag.

Bonds: Bonds are generally considered a safe asset class with more stable returns, but they are sensitive to interest rate changes. In recessions, government bonds can serve as a portfolio stabilizer, especially when central banks lower interest rates, as falling interest rates cause bond prices to rise. In the late cycle, corporate bonds of lower credit quality are often associated with excessive risks. For investors with a short time horizon, short-term bonds can be interesting , while a globally diversified bond exposure is recommended for long-term goals.

Real Estate: Real estate, as a tangible asset, is influenced by economic cycles. It is considered a safe retirement provision and inflation hedge and can generate regular rental income. Historically, downturn and depression phases have been good times to enter the real estate market. Particularly residential real estate remains attractive for institutional investors seeking stable distributions due to rising rents and a structural deficit in the German housing market.

The differing sensitivity of sectors to economic phases and the associated implications for investment strategies underscore the importance of careful portfolio diversification. While cyclical sectors can disproportionately benefit during expansion phases, defensive sectors and certain bond types offer stability during downturns.

The difficulty of timing the market in the short term is well-known. A long-term investment strategy that accounts for cyclical fluctuations is therefore more advantageous for most investors. Regular investments through savings plans or ETFs can utilize the dollar-cost averaging effect by acquiring more shares at lower prices. Patience and adherence to a broadly diversified strategy are crucial to weather short-term fluctuations and benefit from long-term market recovery.

7. Historical Examples and Lessons Learned

The history of the economy is rich with examples of business cycles that, although unique in their triggers, often exhibit recurring patterns in their characteristics and policy responses.

7.1. Great Depression (1929-1939)

The Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash on "Black Thursday" in October 1929, was one of the most severe economic crises in history. Causes included a speculative bubble in the stock market, followed by bank failures and a massive loss of confidence. The US economy shrank by 26% in real terms, and the unemployment rate rose to 25%. Deflationary tendencies exacerbated the situation, as the decline in the price level increased the real burden of debt.

The political response in the USA was the "New Deal" under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This included comprehensive reforms to stabilize the financial sector (e.g., "banking holidays") , massive public construction and infrastructure projects to create jobs , the introduction of social security, and an increase in top tax rates. The New Deal was an example of active interventionist policy that permanently changed the role of government in the economy.

7.2. Oil Price Shocks of the 1970s

The first oil price shock in 1973, triggered by the OPEC embargo, led to drastic price increases and supply shortages. The consequence was a global recession accompanied by a period of stagflation – an unusual state of simultaneously high inflation and high unemployment. Long-term effects included increased investment in alternative energy sources and greater energy efficiency in the affected economies.

7.3. Dot-com Bubble (2000)

The bursting of the dot-com bubble in March 2000 ended a boom in the IT and communications sector. This led to a period of weakness that lasted until about 2004. Many overvalued stocks of companies with unsound business models lost massive value.

7.4. Financial Crisis 2008

The 2008 financial crisis was a global crisis that abruptly peaked in the second half of 2008. Causes included deregulation of financial markets, the issuance of risky mortgages (subprime loans), and a resulting housing bubble in the USA. The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 was a central trigger for the global banking crash. GDP declined drastically in many industrialized countries, including Germany.

Political responses included massive fiscal stimulus packages and expansive monetary policy by central banks, including the introduction of quantitative easing (QE), to stabilize the economy and stimulate lending.

7.5. COVID-19 Recession (2020)

The Corona pandemic in 2020 led to a sharp economic downturn and a (short) recession. The global economy experienced the worst downturn since the Great Depression. However, the rapid recovery was supported by generous fiscal and monetary stimuli and vaccination campaigns.

Historical cycles show that, although specific triggers vary, certain patterns recur. These include speculative bubbles, periods of financial instability, and the need for robust policy responses. Studying these historical events provides valuable insights for anticipating future challenges and developing more resilient economic systems.

Political responses to economic crises have evolved over time. While the New Deal primarily relied on fiscal measures and direct government interventions, unconventional monetary policy instruments such as quantitative easing were widely used after the 2008 financial crisis. This development reflects an adaptation to new challenges and learning from past experiences, but also highlights the ongoing debate about the most effective means of managing economic cycles.

8. Conclusion and Outlook

Economic cycles are an inherent part of the market economy and affect all actors – from individual households to businesses, governments, and central banks. Understanding their phases (expansion, peak, contraction, trough), their different durations (seasonal, business, structural), and the factors influencing them is essential for informed strategic decisions.

The analysis has shown that economic cycles are shaped not only by objective economic data but also significantly by collective psychological dynamics and political decisions. The ability to interpret both "hard" economic data and "soft" sentiment indicators is crucial for accurate forecasts. Historical examples illustrate that, although each cycle is unique, recurring patterns exist, and political responses adapt over time.

For businesses, this means making proactive business decisions and adapting production and investment strategies to the respective cycle phase. For investors, a broadly diversified investment strategy that considers the different sensitivities of asset classes and sectors is of central importance. Long-term thinking and using downturn phases as buying opportunities can help overcome short-term fluctuations. For policymakers, the challenge remains to implement monetary and fiscal policies in a coordinated manner and with regard to time lags to cushion extreme fluctuations and promote sustainable growth.

The economy will continue to be dynamic in the future, influenced by technological innovations, demographic shifts, and global integration. Continuous monitoring of economic indicators and flexible adaptability therefore remain essential to operate successfully in this complex environment and build resilience against future shocks.

Stay sharp and unlock alpha with Gauch-Research. 🚀